Yoga for Osteoporosis: #2 Way to Reduce the Risk of Vertebral Fractures: Strengthening The Trabecular Network

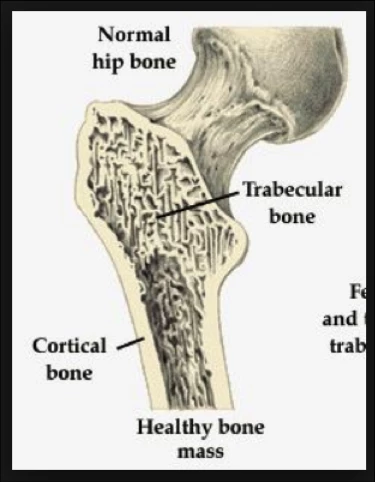

Also known as ‘spongy bone,’ the trabecular network makes up the inner part of the bone, surrounded by a thin outer rim of outer cortical bone (see figure). Trabecular bone has a three-dimensional honeycomb-like structure, which helps with the distribution of compressive and shear forces through the bone, similar to rebar in a concrete foundation.

Vertical trabeculae distribute axial forces (i.e. the vertical gravitational pull on the spine) through the bone. The horizontal plates in the bone, researchers believe, distribute shear stresses, i.e. rotational and lateral pull, transferred from the discs between the vertebrae.

Vertical trabeculae distribute axial forces (i.e. the vertical gravitational pull on the spine) through the bone. The horizontal plates in the bone, researchers believe, distribute shear stresses, i.e. rotational and lateral pull, transferred from the discs between the vertebrae.

Type I Osteoporosis (menopausal osteoporosis) is primarily characterized by a deterioration of the trabecular bone. This happens when more bone is reabsorbed than the amount of new bone that is formed. This in turn transforms the trabecular network into a discontinuous, unevenly distributed mesh, which no longer distributes loading efficiently through the bone.

The loss of trabecular bone after menopause can be considerable. In fact, most of the bone loss with age and menopause happens in the trabecular bone, which declines faster than cortical bone mass. Researchers estimate that women lose 40-50% of trabecular bone mass by the age of 90, compared to a loss of only 20% of cortical bone mass.

This decline is even more pronounced in osteoporosis, and as the vertebrae loses trabecular bone it also loses its mechanical strength and resistance to sudden impact.

Take-Away Lesson. The trabecular bone within the vertebrae is a living structure, which is constantly being remodeled to withstand loads associated with habitual use.

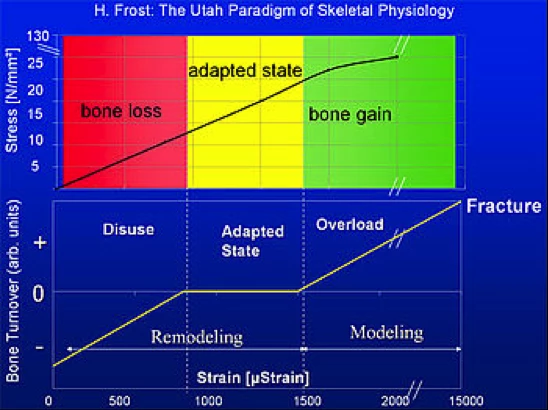

Strong muscles are associated with strong bones, and persistently weak muscles are linked with weak bones. Harold Frost, who developed the Mechanostat theory of bone formation (a refinement of Wollf’s law) defined four levels of bone remodeling resulting from the degree of strain put on a bone. The units of measurements are listed in units of microstrain. (1000 μStrain = 0.1% change in length).

Modeling- and Remodeling Thresholds of Bones

- Disuse: At less than 800 units of micro strain, bone mass and bone strength is reduced.

- Adapted State: Micro strain units between 800 to 1500μStrain: Bone mass and bone strength stays constant, i.e. bone resorption=bone formation.

- Overload: Above 1,500μStrain: At this level of challenge, new bone growth is stimulated and bone mass and bone strength is increased

- Fracture: At Strain above 15,000 μStrain: At this level, bone’s elasticity threshold is exceeded, and bone fracture results.

Importantly, the development of bone tissue and muscle fiber is site specific, that is, it only occurs in the area where the body is challenged. In short, what you don’t use, you lose. Inactivity leads to reduced bone mass and bone strength.

In the absence of sufficient and varied movement of the spine, the muscles not challenged will weaken and atrophy. When no longer challenged by those muscles, bone remodeling turns off and the part of the vertebral body that normally would be challenged by those muscles will weaken.

On the other hand, frequent and varied movement of the spine, such as in yoga, is likely to help counteract bone loss and even stimulate bone strengthening in the osteoporotic spine. Indeed, any exercises that strengthen muscles that support the spine may be useful to prevent or ameliorate the effects of vertebral bone loss.

Indeed, a study by Dr. Loren Fishman and colleagues following 200+ women who were assigned to do a short yoga practice for osteoporosis, found improvements in both the spine and femur in the study group. Dr. Fishman also reported improvements in bone quality, a measure of trabecular bone integrity, measured in a subset of subjects.